Nou Barris is and has been for the last fifty years a core of neighbour resistance, of the fight for their residents’ dignity and organisation to reach basic rights as housing, health, education, transportation, and sewage system. These vindications have been achieved thanks to long and hard, never-ending fights that continue these days intending to improve the daily life of these neighbourhoods of the north suburbs of Barcelona.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

A joint collaboration with Joan Roger Gonce

Associative movement and neighbouring fight history at Nou Barris is closely tied to their neighbourhood’s mere existence since the construction of the first housing cores during the twenty’s at the neighbourhoods of La Prosperitat, Verdum, Charlot, or Can Peguera. The different real-estate promotions that shaped its first urban landscape -formed by one-storey houses inhabited by the immigrants from all around the Spanish State to work at the construction works of 1929 International Exposition and Barcelona’s Metro construction- were followed by strong vindications to reach social improvements and the creation of the first playful, cultural and sporting neighbouring organisations.

During the 1930s, the worker trait of this still sparsely populated area of the Barcelona’s Nord, then it was still part of Sant Andreu district, favoured that Can Peguera’s neighbourhood of cheap houses became the main centre of anarcho-syndicalism and CNT of Catalonia membership, together with the neighbourhood of Torrassa in L’Hospitalet de Llobregat. From the large group of anarcho-syndicalist members, who used to gather at the Munich winery, were formed the diffusion organs ‘Labourer Support’ and ‘Land and Freedom’, reference newspapers of CNT and FAI. With the ending of the Civil War and the dictatorship beginning, the associative life and the neighbouring fights were almost suppressed because of the strong repression and persecution upon all the people linked with the political, cultural, and radical spirit in the diverse neighbourhoods of the actual district of Nou Barris.

It was not until the sixties, with the massive arrival of new worker families from Southern Spain escaping from repression, hunger, and poverty, that these fights were reactivated together with the need to found systems of mutual support to achieve a worthy life for their families. The new vindications arrived as a response to the precarious conditions found by the newcomers. Nou Barris’ residents – who had grown from 30,000 residents in 1950 to over 110,000 in 1960 and increased and overpassed the 200,000 inhabitants during the 70s- faced the housing deficit scraping out a living in shacks and auto constructed houses or living various families under the same roof. It was also during this period that happened the first promotions of public housing of the Obra Sindical del Hogar. These promotions, that transformed the neighbourhoods with the constructions of large buildings, were formed by tiny flats far away from giving a decent house to their new tenants or owners.

Besides their awful housing conditions, the neighbours of Nou Barris saw how the widespread growth and the large speculative constructions that transformed the neighbourhoods were never accompanied by urban planification nor projects of environmental dignification. Most of the neighbourhoods did not have equipment, services, squares neither green nor game zones – beyond the sites full of rubbish where rats proliferated-. The need to dignify these neighbourhoods neglected by the francoist municipal administration was what motivated the neighbours to auto organise and found the basis of movements and neighbouring fights that were developed throughout the 70s, where women had a great protagonism. These fights became a spearhead in the battle for restoring the dignity of their urban environment and also the denunciation of real-estate speculation and the harmful management of the last francoist councils and the first democratic ones.

The first neighbouring fights of the sixties were marked by neighbours’ initiative itself that decided to fix things that the public administration did not care for. Therefore, in the summer of 1964, the inhabitants of the neighbourhood Les Roquetes, that did not have even a sewage system and whose steep streets without asphalt worked as streams full of excrements and rubbish, took action to finish this lack of a basic need. They organised a sewage system, later a system of drinking water, this initiative was known as Urbanise on Sunday (Urbanizar en Domingo). This is one of the most known episodes of their fight to dignify the urban environment, it left iconic images of children carrying big pipes along the steep street and represented the first of many episodes of fighting in the district. The replacement was taken by the neighbours that ended scraping out a living at the shacks of Santa Engràcia’s level, in the neighbourhood of Prosperitat, preys of the real-estate fraud that fought to get a decent house for almost twenty years – since 1964 until the relocation of the last family in 1984-.

The seventies had started heavily marked by the dawn of various neighbouring associations that had the leading role in the different spheres of fight and vindication that characterised the whole decade. Hundreds of protests, closing streets and other visible actions as the kidnapping of buses – the iconic kidnapping of the bus 47 that the neighbours made go up to the top of Torre Baró-, would unify the actions to request sanitary equipment, sportive, educative and cultural, green zones and squares, housing reparations, better communication with the public transport, urbanizations of the streets, ending the shacks and the construction of basic infrastructure. They also fought against the imposition of macro-infrastructures that the local government was selling as an advance for the ensemble of the city, but that was harmful to the neighbourhoods that were still victims of the marginalisation and the systematic neglect by the administration. Because of this, the neighbouring fight was born at the Guineueta Vella against the construction of the Second Belt and to claim the construction of housing of what would end being the new neighbourhood of Canyelles. Along with the fight against the Second Belt, the fight against the asphaltic plant in forestry terrains between Roquetes and Trinitat Nova grew, this plant had to supply the construction of the road axis.

On 9th January 1977, hundreds of neighbours from these neighbourhoods decided to occupy the plant and start the dismantling. The two chimneys were demolished and the electric network was rendered, the tanks, the motors, and the conveyors, forcing the local government to end the task and empty, a building that would end being the future Ateneu Popular de Nou Barris. This athenaeum became a symbol of neighbouring victory, joining the fight against the contamination that produced this plant and the construction of the Second Belt with a vindication for a social and cultural space for the neighbours of Nou Barris. At the same time of these vindications, other initiatives started to give propulsion to the worries of the inhabitants of the district. The creation of schools for adults as the Freire School and the initiative of supporting scholar classes or the promotion of local celebrations, popular libraries, cine forums and hiking groups, theatre or music helped to transform the social and cultural life of the neighbourhoods and their neighbours.

The dawn of these neighbouring movements, protests, actions and initiatives, born as a consequence and reaction to the hard conditions and the neglect and marginalisation led by the municipal administrations, continued with the arrival of democratic councils, increasing with the Olympic Games of 1992. These old and new fights have arrived to our time, fifty years later, with the vindication for improvements for the neighbourhoods and the request of cultural, educative, sportive, and sanitary equipment on track to follow the improvement of collective quality of life in their neighbourhoods and that are still unsatisfactory even though the improvement thanks to the neighbouring fight.

Joan Roger Gonce (Girona, 1984) graduated in History from the University of Barcelona (UB) and Master in Contemporary History from the same university. Since September 2019, he is conducting the studies of PhD from the Polytechnic University of Catalunya (UPC) with the thesis “The revolution of the quotidian and popular labourer surroundings at the district of Nou Barris of Barcelona through the study of the Municipal Census of Residents, 1940-1970. He is the author of various articles, studies, and talks about the social and political spanish and catalan movements throughout the last years of Francoism and the Transition.

Graphic column of a fighter Nou Barris

Interview with Kim Manresa, photographer.

A joint collaboration with Marc Iglesias, journalist.

The social look -marked by the neighbourhood and the reality lived- and the anthropological view -as a result of the interest to know the cultural diversity of his world – are the two main points of the extensive photographic work of Kim Manresa. Born in Nou Barris, he has travelled around the world making reportages and has received many awards and national and international recognition. During his career, Manresa has accomplished more than fifty individual expositions and has published about thirty books.

At the beginning of the seventies, when the newspapers’ photographers rarely walked through the suburbs of Barcelona, a young Kim Manresa became a graphic reporter of various neighbourhoods that started to manifest and fight to dignify their lives.

I am from Nou Barris. I was born in Vilapiscina but when I was thirteen my family moved to Prosperitat, near the shacks of Santa Engràcia, the current square of Àngel Pestaña. Around that time was when my fathers gifted me my first camera. It was made of plastic, simple, those with a square flash that sounded like puff when you clicked them. I started with that camera.

And what photos did you use to take?

In Vilapiscina there were the pools -nowadays a community centre- that were used to irrigate the crop fields situated where now passed the promenade of Fabra i Puig. We went there to have a swim and play with our schoolmates from the National School Madrid and that is where I took some of my first photos.

We talk about the first half of the seventies, right? It was a period of high social and political commotion…

Yes. I was not totally aware of the moment’s political reality, but as the teenager I was, I was asking myself many things. I remember asking my father why the horse police were striking the people when they were doing nothing… He told me, so I could understand it, the shortage we suffered and the demands of the working class. He also talked about the lack of hospitals in the neighbourhoods, the persecution of the Catalan language…

How did your photojournalism career start?

One day we went to a demonstration in Turó de la Peira. It ended with the police charging and I took some photos. After this I met Huertas Claveria. It was presented to me by the neighbouring activists Maruja Ruiz and Andres Naya, who was my protector when I was a child. Huertas was writing a book about the neighbourhoods of Barcelona and bought some of my images. With that money, I got a new camera that was a bit better. Since then, every day after school I went to take photos.

You were so young!

Sure. I started to live off of photography when I was fourteen. At the start, I developed the photos in a lab in Cadí Street, a normal photographic store from that time. I developed two or three rolls until the store asked me to stop because of the presence of police control. The man was scared. He thought that if the police had seen the photos of the demonstrations, they could close his store. So I proposed to my father to assemble a photographic laboratory in the Cadí Street’s flat. I told him that I would pay the rent and the expenses with the money I would make with the photos. My family agreed, thinking that on the weekend I would be coming back with them to Prosperitat. After a month, my father asked: «Aren’t you coming home with us?». And I replied: «You told me that if I was able to pay the rent, the food and wash my clothes, I could stay here». So I lived there.

Did you learn the job alone?

Firstly, I was self-taught, but when I was fifteen I started being the assistant of Colita. Colita was a great photographer and a good friend of Huertas. With her, I learnt many things. At the same time, I also started to work in the afternoons at the Tele/eXpres newspaper. I still keep the graphic editor’s card from 1975. I was a child!

A child that became a graphic journalist of the neighbouring fights of Nou Barris…

It was almost unconscious. This period –that lasted till I was eighteen– was when I made a series of photos about manifestations and neighbouring fights. It was the time when there were more demonstrations. The mobilisation was high these days and intergenerational. Everyone was demonstrating, closing streets… Nowadays, people demonstrate on social media.

Do you miss it?

These days there was a different model of coexistence and social harmony now lost. The solidarity was key. We lacked material things, but the community was so strong. My childhood was very happy. We played on the street, we rode on cardboards down streets full of mud, we slept in caves… It was not necessary to make an appointment to meet with someone or have dinner together.

And what do you think about Roc Blackblock’s mural on the Ateneu? What was a live report now is part of a project dedicated to memory…

Personally, the fact that a photo I took fifty years ago has gained importance again is incredible. When I took it, I knew the family and I was a friend of some siblings. They were getting ready to go to one of the demonstrations to claim decent housing at the shacks of Santa Engràcia. ÉIt is wonderful that now my photo has become a mural because recovering the memory is very important. If we lose the memory, we lose the identity.

When you took photos, did you imagine that that register would acquire the documental value it has today?

No, I don’t. I was so young. I liked what I did, but I was not conscious of the importance my work would get through the years.

Nowadays, when you look through these images, do you see them the same?

Yes. This has not changed. In fact, problems are the same. Evictions, scarcity… I have photos of evictions in Valldaura’s promenade in 1975. People were throwing furniture to close the street… Today we have mobile phones and social media, but the reality has not changed at all.

WORK PROCESS

2022 is going to be the 45th anniversary of the Popular Atheneum of Nou Barris (Ateneu Popular Nou Barris), it is also ten years after the fulfilment of the big mural on the stage box, the largest building of the atheneum, by the artist Roc Blackblock. With the consolidation of the project Murs de bitàcola and alignment of these three elements, we agreed with the Atheneum to paint a mural about not only the sociocultural centre, but also that would reflect the popular memory of the neighbourhood, where the Atheneum was born and to whom it owes its existence.

The working process started with a meeting with neighbourhoods, members of the Bidó of Nou Barris (the entity that manages the Atheneum), workers, users, and other entities as the Youth Casal of Roquetes. This was done to share the different views about the neighbourhood and its values, as well as define the direction and line of the mural, with the goal of communicating a story about the rich history of the zone. Throughout that meeting came up many ideas about remembering how the neighbourhood has had to fight for every inch of street, to achieve every improvement (sewage system, streetlights, public transport, schools…). It was also talked about the importance of vindicating the periphery condition, a zone that is usually forgotten.

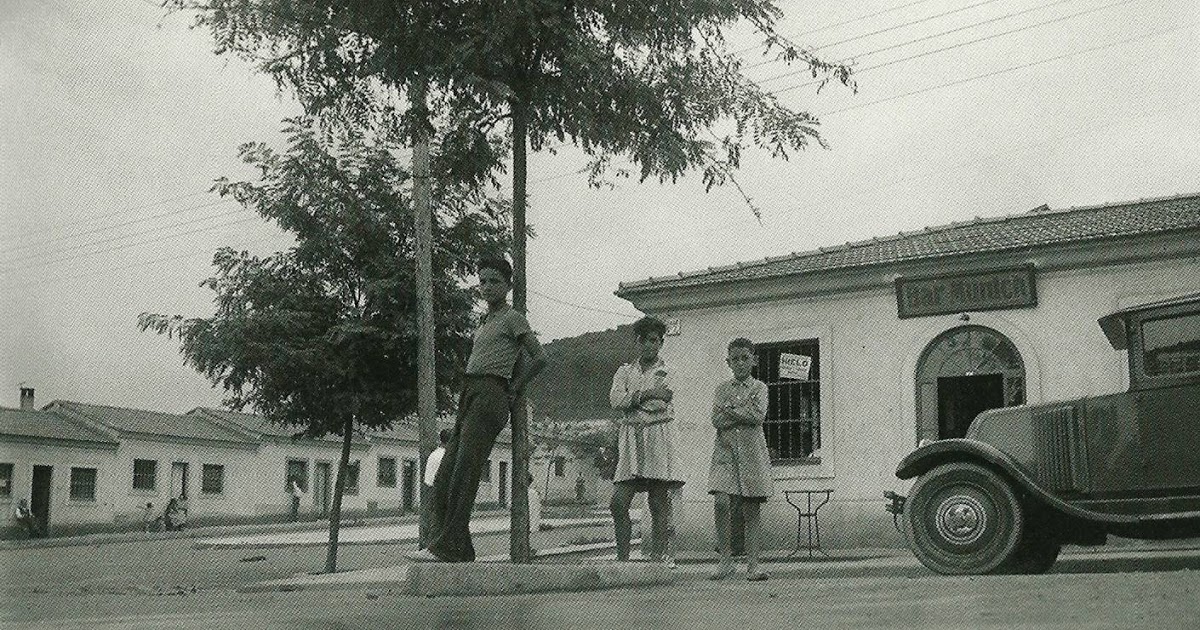

Later we had access to the photographic archive of Roquetes to look at images that would illustrate the story of the social fights of the last fifty years. We received excellent accompaniment by a member of the archive because of his knowledge about the history of the zone. Thanks to the visit, we had a large selection of photos with which we were able to develop five designs that we shared with the Atheneum so that the community could choose their favourite one. The theme was shared by all the designs; the social fights and the communal vindications of the last years; each one was focused on a different area of this collective memory. We decided that all the designs should keep the typographic intervention of the Colectivo almorrana made through the first years of the Atheneum that followed an artistic participatory process where the community provided words and concepts that were reflected on the facade. It is an iconic work of art that adds value to the new mural. In the end, the choice came to be an image of the celebrated photograph from Nou Barris Quim Manresa, he has portrayed the reality of his surroundings since his childhood, the shacks of Santa Engràcia, a series that conformed to a book of legendary photographs. One of them became quite famous, a little girl with a placard that said “yes to flats, no to shacks”, but we chose the image that was painted because it was a vivid image of the communal feeling: it is not a single character but the force of the community, the network, and the group that made Nou Barris strong.

After deciding the design, we started the intervention that lasted ten days of hard work. Throughout these days we enjoyed the pleasure of welcoming the visit of Pepi and Charo, two of the protagonists of the photography, who still live in the neighbourhood and were able to recognize themselves and their families in the mural. They did not remember the moment the photo was taken because it was a brief moment, but through the years they had thought of them as the images have become famous, and somehow they have become the living narrators of recent history. When we asked about that time, they remembered bitterly their grandfather, emigrant and modest as many others, he spent his savings in a flat that was never built because the construction company ran away with the money. Although it was a bitter memory because many people lost everything, they were young and life seemed easier and happy.