The fight is not over

An article by David Gesalí and David Íñiguez

January 25, 1939; just one day before the loss of the city of Barcelona for the Republic, chaos took over the capital. The Republican general staff had decided that Barcelona will not resist and that the defense will settle in the mountains further east, inducing a general feeling of defeat.

Further north, La Garriga will become part of a vertical axis that, passing through Vic and Puigcerdà, will have to become strong. For the preparation of military operations, the aviation workshops, its two military hospitals, and a series of offices and military entities, including the army transmission school, have been evacuated from La Garriga. But it’s not an escape, it’s a preparation for final resistance. While some retire, others fight or prepare to join the fight.

That day, over the sky of the Rosanes’ airfield, the last great air combat of the Spanish war takes place. During 45 minutes, the buzz of more than a hundred planes simultaneously flying in the sky will be the epitaph of the Republican wings in La Garriga. At the end of the battle – with several planes shot down on both sides – the small Republican fighters will march towards Girona’s airfields. This will put an end to a frantic week in which the command of the air defense of Barcelona and, by extension, of the entire Catalan republican territory, has fallen on the airfield of La Garriga and its facilities as the headquarters of the fighter squad. The support trucks of the combat air unit, like a long caravan of a circus, climbs towards Celrà and Sant Julià de Vilatorta. In La Garriga, the aviation squat lets in the staff of the fifth Republican army corps and Lister, its charismatic leader.

The withdrawal of civilians to France and the retraction of republican troops is a subject widely dealt with by literature, but it is not a particularly researched topic. It is for this reason that both researchers persist in knowing the movement of the republican forces in the blockade that will make the withdrawal from Barcelona to France last for fifteen days. The definitive offensive on Catalan soil consisted of 55 days of fighting of a powerful army in the service of Franco against decimated republican remains, in a series of fighting of greater or lesser intensity that we call withdrawal or abandonment. The following year the considered most powerful army in the world, the French, fell in 40 days to German troops. In France, the period is extensively researched and historical.

The International Brigades, those volunteers from all over the world who came to Spain to fight for the Republic, were withdrawn from the front in 1938, in the midst of the Battle of the Ebro, in a desperate attempt by the Republic to turn the war into a domestic affair without the participation of foreign powers. These volunteers ended up concentrated in different towns in Catalonia and in the Llevant area, waiting to be repatriated. From the repatriation there were three different situations: the wounded; those who could return to their countries without excessive problems and those whose countries had taken away their nationality or were simply fascist countries where they would be arrested, tortured and killed or, at best, imprisoned. These were the German, Austrian, Hungarian, Balkan, Italian brigadiers, etc. These remained inactive in the so-called centers of cantonment, waiting and watching as the Republic agonized without being able to do anything. The truth is that if defeat was consummated, they would be left without land to live on. Within their reality, they had no choice but to fight or die.

On January 25, 1939 —simultaneously to what is explained above— there was an event of historical relevance:the regrouping of the International Brigades in la Garriga,an event that has been erased from history, or perhaps considered irrelevant, because it has not been considered that these troops had any combat or some kind of significance within the republican withdrawal. Nothing could be further from the truth. Luigi Gallo (Longo) had been working for days to regroup the internationals for the defense of Barcelona. On the 21st, a ship loaded with international fighters from the central area (129th brigade) had arrived from Valencia, many of whom wanted to be repatriated, although others would join the alleged defense.

Also on the 25th, Gallo sends a letter to General Modesto, head of the Ebro Army, informing him that he has a number of international soldiers who have already arrived at the concentration site, La Garriga, in order to recompose the mythical 35th Republican Division and participate in military operations. On those frantic days, trains from the Ripollès and Osona docking centers unloaded the troops at the town’s station. From the quartermaster’s center in Vic came uniforms and groceries in order to nourish and refresh the fighters.

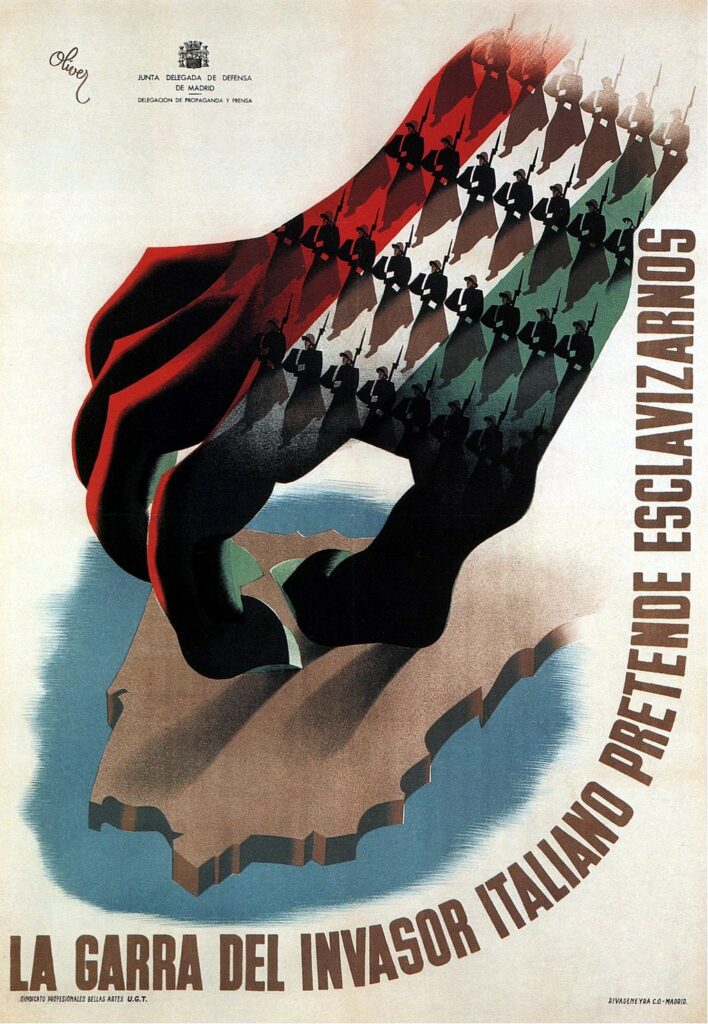

Unfortunately for the intentions of the contingent of internationals, the Republican General Staff considered Barcelona an indefensible city and proposed an orderly withdrawal that was impossible to execute, resulting in a great abandonment in the Maresme area. The 35th division, which at the time was a Spanish unit, was the only good unit that could oppose the thrust of the Italian division Littorio of the CTV (Corpo Truppe Volontarie). The idea of using international soldiers to stop the enemy advance takes shape and accelerates, because republican generals clearly see that they have nothing to oppose the enemy’s free advance through the Barcelona counties. Quickly reinforced with international soldiers, it was sent to the area of Arenys on the 27th, where it was able to slow down the front for three days. In the area of la Garriga the rest of the international soldiers were constituted in the 44th division, due to the same pressure of the front it entered into combat in the area of Les Franqueses-Caldes de Montbui, leading to hard fighting in which its commissar Ernst Blank lost his life..

On the 29th of January, the penetration of Italian troops from the Green Arrows division towards Hostalric generated a withdrawal order. This leads to the withdrawal to the second line of the internationals of the 44th division in the area of Arbúcies and the progressive of the 35th in order to create a new powerful international unit. The Italians’ knowledge of the CTV of the fact that La Garriga is a concentration center for international troops makes them request their air force, the peninsular legionary aviation,to carry out a bombing of the town of la Garriga. The bombing by ten Savoy S79 aircraft will not cause casualties for international soldiers, but it will cause the deaths of 15 civilians and much destruction all over the village. The collapsed station will be one of the iconic images of that destruction. On the 30th, pressure in the Maresme pushed back the republican troops beyond the Tordera river, and those of la Garriga began their evacuation through the south and north of Montseny. On the 31st, with the loss of Collsuspina, the evacuation took on a desperate look.

On February 2, a brigade of the 44th division successfully fights in Riudarenes, where the Italians fascist of the CTV notice strong resistance, which increases their concern. Certainly, the Italian fascist units had had very few casualties from the beginning of the battle for Catalonia to the clash at the Montalt in Arenys, and now, suddenly, they found a very tough nut to crack. On the night of the 2nd to the 3rd, the 35th division fought hard for Llagostera which they will lose in the early hours of day 3. Mussolini, due to the harshness of the fighting, will be promoted by General Gambara, head of the CTV, and General Bitossi, head of the Littorio division, who leads the fighting against the internationals of the 35th.

February 3rd will be the day of the great and last battle for Catalonia. The Republicans will concentrate all their international troops in Cassà de la Selva. The 44th division is disbanded and instead a single 35th international division is created under the name of the 35th Division of the Ebro Army Reserve, which will be reinforced with the scarce artillery available and a small group of armor. His task will be, theoretically, to defend Girona. The real one, to slow down the enemy’s momentum again in order to make an orderly evacuation of the media, which may be used to continue the war in Madrid or Albacete. The hard battle begins at dawn. Over the course of the day, Italian artillery will launch more than two thousand howitzers, which gives us an idea of the crash. The maneuver to conquer Cassà will be costly for fascist troops to intensively use their best professional soldiers. The casualties on both sides will be numerous and so will the wounded, and to all these we will have to add the dead civilians. The battle will end at seven o’clock in the afternoon, with the conquest of Cassà and the free path to reach the city of Girona that will fall the day after that. Among the wounded, General Bitossi who received a burst of machine guns, marching ahead to encourage his troops who, in the early afternoon, could not advance due to international pressure.

On The 4th, the internationals will continue to hinder the progress, but they will do so spontaneously, not coordinated. Italian General Gambara himself concludes that the Republican defense has been a strong and organized line of defense, not a skirmish, and will ask that no more opportunity be given. The last battle is that of the internationals and, interestingly, that of a fully international 35th division that will have lasted one day: the one of its true epitaph.

Given these facts, what happened in la Garriga on January 25th cannot, in any case, be considered anything anecdotal.

David Gesalí Barrera (Barcelona, 1964) has a degree in History from the UAB and a master’s degree in teaching social sciences and heritage from the UB. He belongs to the Consolidated Research Group of the University of Barcelona (SGR 945) DIDPATRI, researcher at ADAR and SHYCEA. He is a specialist in the history of aviation and war in Spain, a subject on which he has published more than a dozen books and numerous articles.

David Íñiguez Gracia (Barcelona 1971) is a professor at the Faculty of Education and a researcher at the University of Barcelona, a PhD in Didactics of Social Sciences and Heritage and won an Extraordinary Award from the Faculty of Education of the University of Barcelona (2010). He belongs to the Consolidated Research Group of the University of Barcelona (SGR 945) DIDPATRI, Didactics of Heritage, and he is the author and co-author of more than fifteen books on the Spanish War.

Both authors are regular collaborators, and together they have participated in numerous conferences and dissemination spaces. In the museographic and heritage field, they have participated in the drafting and execution of various projects and museum interventions, such as the museumization of the air-raid shelter of the station in la Garriga, the Rosanes airfield or the la Sénia airfield, in addition to the Interpretation Center of Republican Aviation and Air War, CIARGA in Santa Margarida and els Monjos.

THE WORKING PROCESS

This intervention on the passage of the International Brigades through La Garriga is unique and special for our project. It is one of those that has not been a commission, but rather our own proposal that we have launched from Murs de Bitàcola, as in many other locations, with the desire to start carrying out the Brigadistes project. It must be said that the reception of the City Council has been fantastic: we have been accompanied at all times by Enric, culture technician, which has allowed us to get to know an episode as impressive as the one David Gesali writes about in his article.

Regarding the technical and executive part of the project and the mural, it has been very special since we have had to face several challenges. The first one has been the dimensions and characteristics of the wall, which was long but very low, with some sections of bricks that were up to one meter and a half long. This led us to use brushes (plastic paint) instead of spray paint, which is what we usually use, to be able to achieve better precision and detail. Also, because of the landscape format of the mural, it required us to make many images that contained a large amount of detail. This is why we resorted to brushes, although the texture of the wall made it difficult to achieve a high level of detail. Nevertheless, we are very happy with the result.

The other challenge we have faced has been how to illustrate the importance of La Garriga in the Civil War and, especially, in this last so special episode of reunification of the International Brigades, as well as the bombing. At the time of recounting these episodes, the challenge has been that we did not have any photographs documenting these historical moments, except for the one of the bombed train station. To solve this, we decided to allow ourselves the license to use photographs that somehow illustrate these episodes, even though they were not strictly taken at the airfield of La Garriga, nor did they show the nurses who were working at the Hospital of La Garriga. Neither did the image of the train correspond to that moment when the brigadiers arrived at La Garriga ready to maintain a line of defense against fascism.

As we have been fortunate to have the advice of David Gesali, we have tried to use images that, although not strictly belonging to these episodes, do not incur any inconsistency. Thus, we changed the image of the airfield because in the first one the airplane that came out was not like the ones that could be found at the airport of la Garriga. The same happened with the image of the nurses, a photograph of a group of nurses in front of an ambulance given by the Canadian people to the Spanish Republic: we decided to remove the inscriptions it initially contained because we were not sure that such an ambulance had ever circulated in la Garriga. We understand that this is an artistic license with the purpose of spreading all of this information and knowledge.